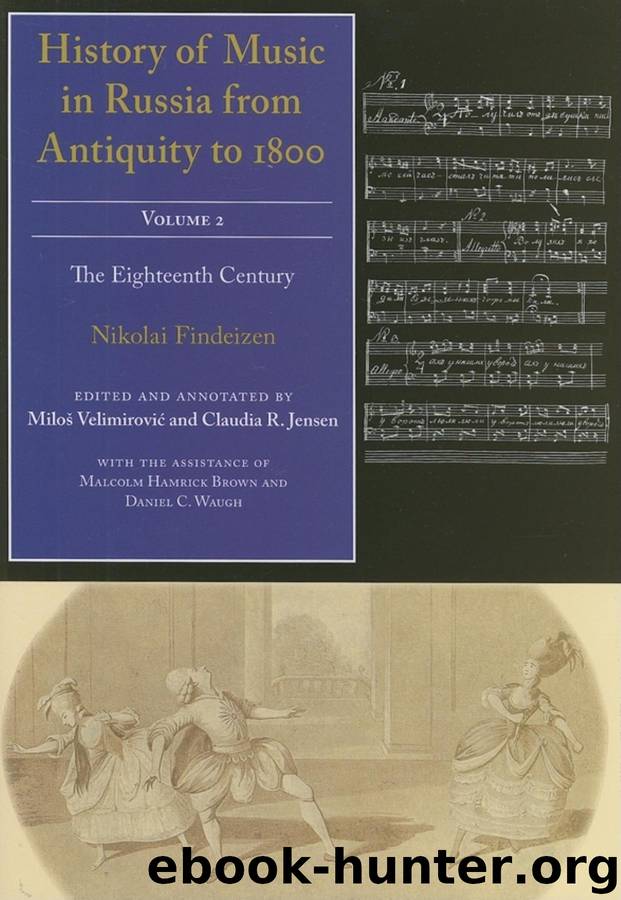

History of Music in Russia From Antiquity to 1800, Vol. 2 by Nikolai Findeizen Milos Velimirovic Claudia R. Jensen

Author:Nikolai Findeizen,Milos Velimirovic,Claudia R. Jensen

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Indiana University Press

Published: 2016-06-22T16:00:00+00:00

Our ritual and fortune-telling songs prove even better that we borrowed a great deal from the Greeks in our folk singing. The ancient Greek games and songs to this day known as Klidona are the very same thing as that which we call the fortune-telling songs.

Among the Greeks the Klidona consisted in prophecies about the future, whether lucky or unlucky in marriage or in love. The assembled Greek women each tossed their rings or coins into a dish, which were then taken out while the women sang songs, and whatever text was sung as a ring was being taken out of the dish, that [event in the text] was going to happen. We do the same when singing podbliudnye songs, with the only difference that in Greece they tossed tokens into a dish filled with water whereas we do it in a covered dish.

For the Russian Klidona, the Slavs added their favorite refrain, which the Greeks did not have; they sang as we do “slava,” which is the main deity of the Slavonic people and whose name was borrowed not only for great deeds but was often used in songs and in the naming of people.

Live, live Kurilka is a kind of Greek game, used among the ancient Greeks between wedding games.

N. A. L’vov’s discourse cited here was repeated almost verbatim by M. Guthrie in his Dissertations sur les antiquités de Russie (St. Petersburg, 1795), but it was attributed to Prach, not to L’vov. No doubt Guthrie had to recognize Prach as a contributor to his volume for placing at his disposal some of the folk songs he had written down. Curiously Guthrie cites a few songs in similar harmonizations, songs totally absent from either the first or the second edition of Prach’s collections. Guthrie includes two dance songs (one from Great Russia and the other from Ukraine) and a military (soldiers’) song, and he gives their tunes in his musical supplement on a separate staff but without text. Apparently these tunes appeared in Guthrie’s book unconnected with the circle of music lovers that gathered in N. A. L’vov’s home. Yet Guthrie cites the melody of the ancient Greek ode by Pindar, first published in Kircher’s Musurgia universalis (1650), with the same tune and manner of performance (starting with a soloist followed by the choir) that N. A. L’vov used in his comparison with a protiazhnaia song.369

To finish up with Guthrie’s book, it should be pointed out that, for its time, this work represented a substantial musical and ethnographic collection, dedicated not only to folk song but to folk musical instruments and folk customs and beliefs. For the ethnographic data, Guthrie probably utilized the contemporary works by M. V. Popov (d. ca. 1790).369A It is also interesting to take note of chapters dealing with folk songs, dances, and musical instruments. In chapter 3 Guthrie added representations of eleven musical instruments that could be found in folk usage at the end of the eighteenth century (rozhok, dudka, zhaleika, svirel’, Siberian horn, bagpipe, balalaika, gudok, gusli, lozhki, and performance on a double dudka-type reed pipe).

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Aircraft Design of WWII: A Sketchbook by Lockheed Aircraft Corporation(32286)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(31916)

Call Me by Your Name by André Aciman(20498)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19052)

The Art of Boudoir Photography: How to Create Stunning Photographs of Women by Christa Meola(18613)

Shoot Sexy by Ryan Armbrust(17720)

Plagued by Fire by Paul Hendrickson(17405)

Portrait Mastery in Black & White: Learn the Signature Style of a Legendary Photographer by Tim Kelly(16996)

Adobe Camera Raw For Digital Photographers Only by Rob Sheppard(16969)

Photographically Speaking: A Deeper Look at Creating Stronger Images (Eva Spring's Library) by David duChemin(16683)

Ready Player One by Cline Ernest(14643)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14488)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14057)

The Goal (Off-Campus #4) by Elle Kennedy(13657)

Art Nude Photography Explained: How to Photograph and Understand Great Art Nude Images by Simon Walden(13031)

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11812)

The Priory of the Orange Tree by Samantha Shannon(9064)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8974)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8893)